The fabled Golden Record of Voyager heightened the fascination. The two Voyagers each carried a phonograph record of images, music, and sounds representative of our planet, including spoken greetings in 55 languages to any intelligent life-form that might find them. This was a message from Planet Earth vectored into the Milky Way—a hopeful call across space and time to our fellow galactic citizens. It thrilled to think that news of us and our home planet might be retrieved by some extraterrestrial civilization, somewhere and sometime, in the long future of our galaxy.

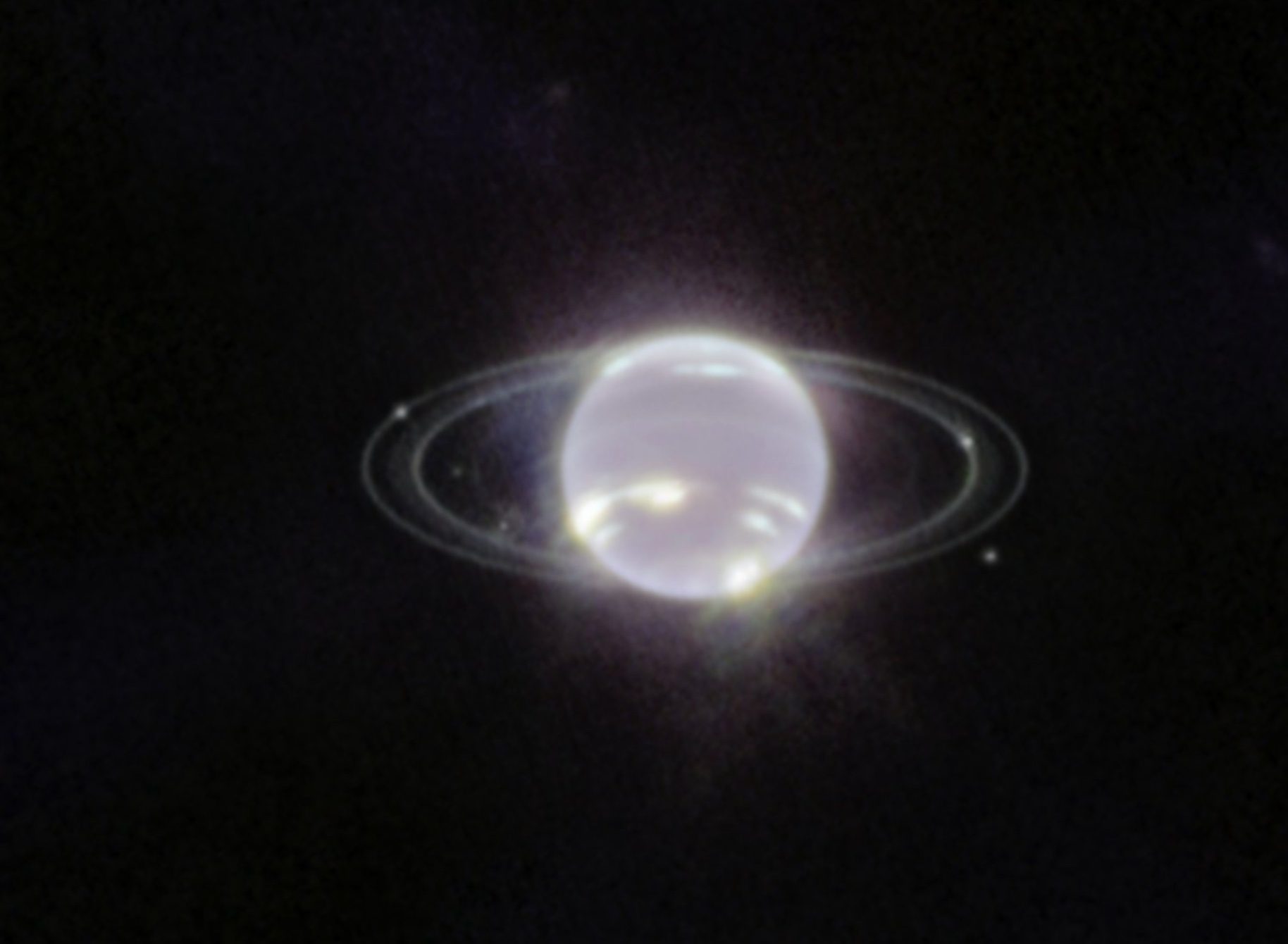

Because of its never-ending journey, its dazzling scientific discoveries in the solar system, and its human-forward countenance, to participants and onlookers alike, Voyager became symbolic of our acute longing to understand our cosmic place and the significance of our own existence. It left no question of our status as an interplanetary species. It is, even today, the most revered and beloved interplanetary mission of them all, the Apollo 11 of robotic exploration.

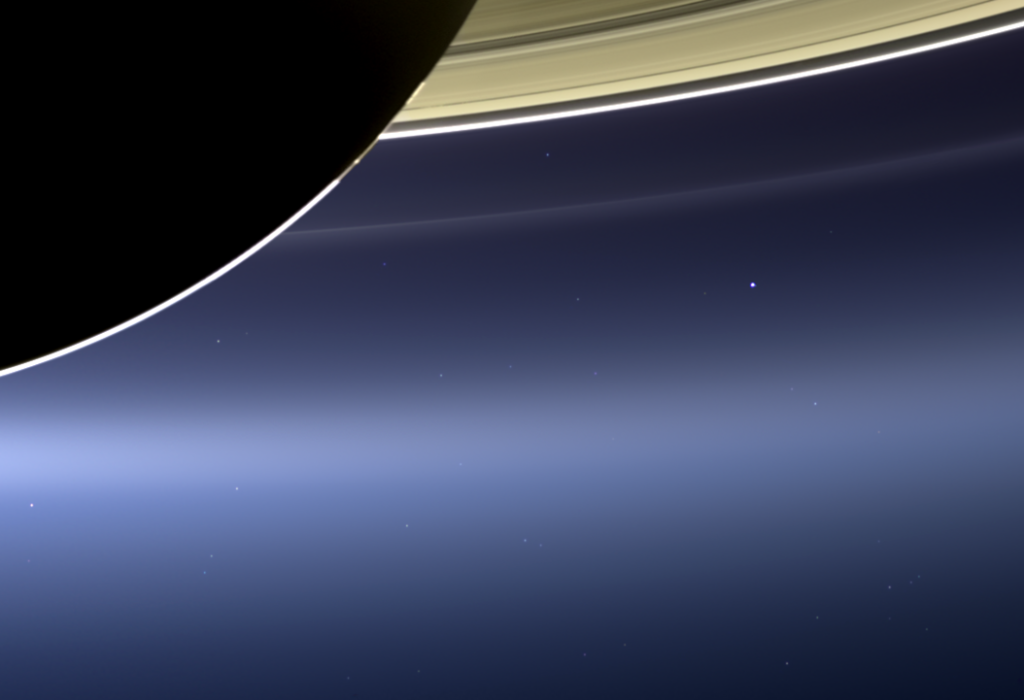

Perhaps the most poignant gesture of the Voyager mission was its final parting salute to its place of birth. The portrait of the sun’s family of planets taken in early 1990 included an image of Earth. Carl Sagan, a member of the Voyager imaging team and the captain of the small team that had produced the Golden Record, had proposed this image to the Voyager project in 1981. He eventually called it, appropriately, the Pale Blue Dot. His motivation is expressed in his book of the same name, in which he describes wishing to continue in the tradition begun by the famous Earthrise images of the Apollo program, referring specifically to the one taken from the surface of the moon by Apollo 17. Then, he continues:

It seemed to me that another picture of the Earth, this one taken from a hundred thousand times farther away, might help in the continuing process of revealing to ourselves our true circumstance and condition. It had been well understood by the scientists and philosophers of classical antiquity that the Earth was a mere point in a vast encompassing Cosmos, but no one had ever seen it as such. Here was our first chance.

Though Carl had convinced a small group of Voyager project personnel, and imaging team leader Brad Smith, to provide the required technical, planning, and political support, the project leaders were not willing to spend the resources to do it. Carl’s 1981 proposal was rejected, as were his other proposals over the following seven years.

Completely unaware that Carl had initiated such an effort, I was independently promoting the very same idea—to take an image of the Earth and the other planets—soon after I became an official imaging team member in late 1983. I had in mind the sentimental “goodbye” that would lie at the heart of any image taken of our home planet before Voyager headed out for interstellar space, and the perspective it would give us of ourselves—our small and ever-shrinking place in Voyager’s ever-widening view of our cosmic neighborhood. Also, the “cool factor” in presenting a view of our solar system as alien visitors might see it upon arrival here was another draw.

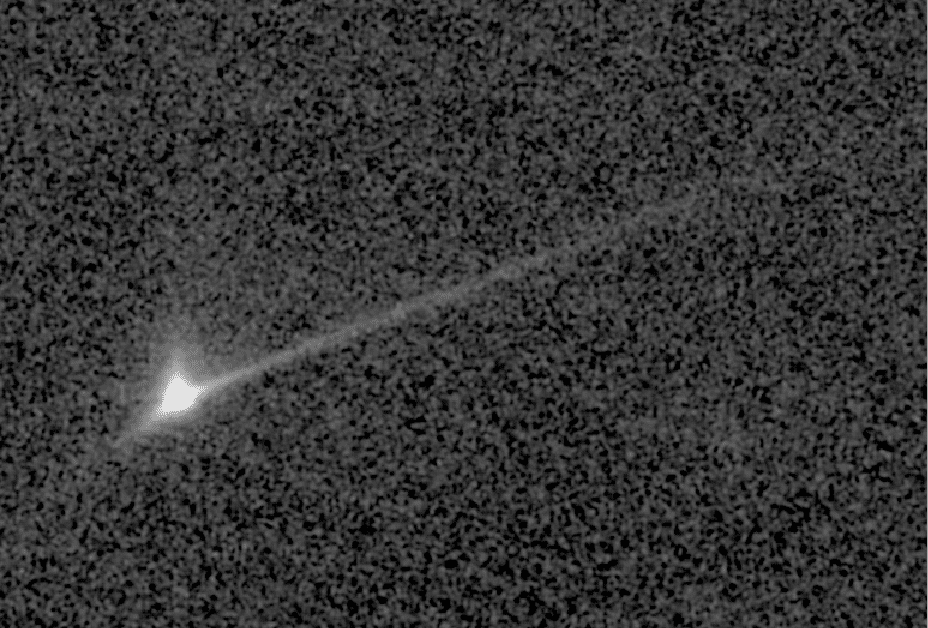

For two years, I hawked the idea around the project and, not surprisingly, like Carl, got nowhere. But Voyager’s project scientist, Ed Stone, did his best to encourage me by advising that if there was some science to be obtained by an image of Earth, it might then be possible. As I couldn’t think of any, I gave up and began instead thinking of other scientific observations of the inner solar system that could be made from the outer solar system. The result: In 1987 we used Voyager 1 to attempt to image the asteroidal dust bands discovered by the Infrared Astronomical Satellite in 1983. Regrettably, nothing was detected.

It wasn’t until 1988 that I finally became aware of Carl’s proposal. After telling him that I had had the same idea a few years earlier—and, like him, tried and failed to get it jump-started—he requested my help, suggesting that I compute the exposure times. (A letter I wrote to Carl after our conversation, in 1988, summarizing that conversation and reporting on my calculations, is archived in the Library of Congress.)

It is an ironic historical footnote to this story that the most difficult calculation of the bunch was the exposure for the Earth. As no spacecraft had ever taken an image of Earth when it was smaller than a pixel, and since the cloudiness of its atmosphere is so variable that its inherent brightness is hard to calculate or predict, there was no information available then to suggest confidently how long an exposure should be. Somehow, it all worked out.

The Pale Blue Dot image of Earth is not a stunning image. But that didn’t matter in the end, because it was the way that Carl romanced it, turning it into an allegory on the human condition, that has ever since made the phrase “Pale Blue Dot” and the image itself synonymous with an inspirational call to planetary brotherhood and protection of Earth.

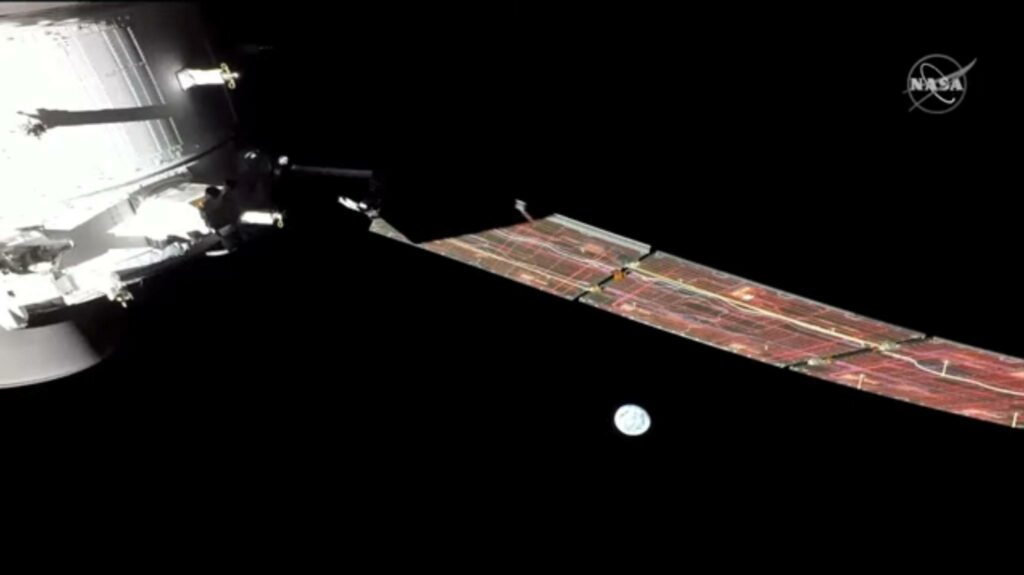

And we did all that—on July 19, 2013.