The Guardian published 30/4/2023 by Tim Adams

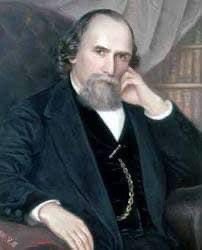

Anthony Selon, the distinguished historian and headteacher, discusses his latest book about a contemporary prime minister, a devastating – and dispiriting – account of Johnson’s chaotic reign

Sir Anthony Seldon, the famous headteacher, has been writing book-length report cards on British prime ministers for 40 years. The latest, on Boris Johnson, based on the accounts of more than 200 people who witnessed his catastrophic, clown-car time in office first-hand, is a test not only of Seldon’s method, but also his tone. In previous volumes the author has assumed a base level of gravitas in his subjects, and of structure in their government. Though he employs the same quasi-legal model for his inquiry here, gathering careful evidence, weighing judgments, the story he pieces together is often one of venal mayhem; it frequently reads like a considered constitutional appraisal of rats in a sack.

There is a telling coincidence in the fact that the first indelible report of Johnson’s behaviour was also the work of a school master. Martin Hammond’s infamous notes on Johnson at Eton, which recorded his “disgracefully cavalier attitude”, his “gross failure of responsibility” and his deep-seated belief that he “should be free of the network of obligation that binds everyone else” is the opening source of Seldon’s account. Johnson’s “end was in his beginning”, he argues. Speaking to me about his book last week, Seldon noted that Hammond – who had been the “formidable pipe-smoking” head at Tonbridge school when he started out as a teacher – was a longstanding inspiration, both as an educator and a writer. “Two things,” he says. “One is that his report was typically acute and detailed, like a psychiatrist’s analysis. And second: just how much the character is formed very early on.”

Seldon is very well placed to offer the much fuller version of that analysis. He came to national prominence as a thinker on education as head of Brighton college and then Wellington college. He recently returned, at 69, to his former day job by agreeing to take over the headship of Epsom college after the murder of Emma Pattison and her daughter in February. The day we meet is the day before the new term at Epsom, where Seldon has an 18-month contract. The aim, he said on taking the role, would be “to provide the confidence, stability and maturity to see the school through the aftershocks of the deaths of Emma and Lettie Pattison”.

In recent years, Seldon has experienced some of the effects of instability and grief on a personal level. His last book before the volume on Johnson was a thoughtful, heartfelt journey on foot along the western front of the great war. He undertook it, he wrote at the time, because his endlessly busy life had come unmoored. He had lost his beloved wife to cancer in 2016 and had quit his job as vice-chancellor of the private University of Buckingham after disputes with the board. Though he had long been a proponent of teaching wellbeing, “enduring peace” eluded him. He traced some of that disquiet back to the fallout of anxiety and depression that was a legacy of his maternal grandfather, who was badly wounded in the first world war. The walk was an exorcising of demons. “Could I change to a less manic gear?” he wondered. “Writing a book on Boris Johnson, as planned, if I was to keep up my rhythm of books on recently departed prime ministers, would hardly help me do this…”

Seldon is far too rigorous a historian to let that backstory seep into his account of Johnson in office (which was co-written with the historian Raymond Newell). However, you have a strong sense reading it, talking to him, that the soul searching fuelled his efforts to capture the exact nature of Johnson’s irresponsibility in office. Seldon is a man who has devoted his life to understanding and nurturing the kind of emotional intelligence and civic responsibility from which society can be woven. Johnson represents the wilful rupture of those beliefs. Talking about him, Seldon acknowledges the former prime minister’s charisma “lights up the room”, but you sense too his almost personal feeling of betrayal at the squandering of those gifts, that headmasterly reaction that Johnson had let down his school, his family, his nation, but most of all, himself.

Of the 57 people who have held the highest office, Seldon suggests, Johnson was probably unique in that he came to it with “no sense of any fixed position. No religious faith, no political ideology”. His only discernible ambition, Seldon says, was that “like Roman emperors he wanted monuments in his name”.

“To those many people who say, ‘Of course he believed in Brexit’, the evidence is absolutely clear,” Seldon says. “From the beginning it was striking that he believed that there was a cause far higher than Britain’s economic interests, than Britain’s relationship with Europe, than Britain’s place in the world, than the strength of the union. That cause was his own advancement.”

The eyewitness reports of events in Seldon’s book expose once and for all the great con of the referendum campaign that has so savaged the country and its economy. We learn from many named and unnamed sources that even Johnson was outraged by some of the stunts pulled by Dominic Cummings in the name of Vote Leave. Confronted with the xenophobic – and untrue – scaremongering that Turkey was about to join the EU, one confidant reports that “[Johnson] wanted to come down to London and apparently punch Cummings”. On the morning of the referendum result itself, Seldon writes, Johnson “paced around in a Brazilian football shirt and misfitting shorts looking ashen-faced and distraught. ‘What the hell is happening?’ he kept saying… Soon after, stopping in his tracks, a new thought struck him: ‘Oh shit, we’ve got no plan. We haven’t thought about it. I didn’t think it would happen. Holy crap, what will we do?’”

Johnson’s eventual solution to getting Brexit done as prime minister was to bring in Cummings to do the work that he had no appetite for, in the full knowledge that his chief adviser was a wholly destructive force. That, Seldon, suggests to me, was another first for British political leadership:

“There has never been a prime minister who has been so weak to have ceded so much power to a figure like Cummings. Here was someone who went ahead and removed the chancellor of the exchequer, to replace them with someone more biddable. Who knocked out the cabinet secretary and head of the civil service, appointing someone unable to assert himself. Who tried knocking out and appointing his own person as governor of the Bank of England, and as head of MI6. While all the time expressing contempt for Johnson.”

The book describes how after the 2019 election Cummings assumed universal power across government as Brexit and then the pandemic unfolded. (Johnson at one point raged impotently that: “I am meant to be in control. I am the führer. I’m the king who takes the decisions.”) Unwilling to confront his chief of staff directly, it is said that Johnson frequently employed the excuse that he was subject to the “mad and crazy” demands of Carrie, his fiancee upstairs. (In response to the book a spokesperson for Johnson described that allegation as “malevolent and sexist twaddle”.)

Seldon suggests now that the results of this chaotic approach “took us back to a pre-1832 world of court politics when the idea of a programmatic government with a series of policies and beliefs hadn’t yet been formed. It was just a milieu of shifting alliances and factions.” One of the striking aspects of his book is that the world beyond the confines of No 10, the reality of unprecedented national crisis in millions of people’s lives, hardly ever gets a look in, so concerned are the principal actors in this drama with protecting their sorry backsides.

Johnson could have been the prime minister he craved to be, but he wasn’t, because of his utter inability to learn

Cummings was one of the few participants in that Downing Street and Whitehall farce who did not speak to Seldon. The author does not feel that the omission is significant, since Cummings has written so very much about this period, “and his footprints are over everything anyway. People will make their own judgments,” he says of what he discovered, “but I don’t think that it’s remotely unfair to Cummings or for that matter to Johnson.”

The most dispiriting thing about reading the book is that dawning sense that all your worst imaginings about the conduct of that government were, it seems, played out in real time. Seldon argues that the double act in the oven-ready years of prorogation and Barnard Castle really did deserve each other, even if none of us deserved them.

“I suppose at least Cummings did believe in Brexit, although ultimately, really, did he?” he says. “From everything we heard [for the book] it just seemed Cummings was full of hatred. He probably hates himself; he certainly hates other people. He wants to destroy everything. Johnson in his own way never knew what he stood for, but he shared that contempt for the Tory party, contempt for the cabinet, contempt for the civil service, contempt for the EU, contempt for the army, contempt for business, contempt for intellectuals, contempt for universities.”

About a decade ago, Seldon, who is a governor of the Royal Shakespeare Company, began an informal programme with David Cameron’s government that sought to provide for the present incumbents of the highest office some history of No 10 itself and their predecessors there. He staged a series of talks from prominent historians, as well as performances of Shakespeare in the rose garden, in the belief that politicians “might root themselves in the arts, in the benchmark of what is good and true”. He recalls a performance that the RSC gave for Cameron and guests just before the former resigned as prime minister: “It was quite a moving occasion in the garden. The killing of Caesar was one of the scenes and I remember watching Cameron with his daughter leaning on his shoulder and Samantha next to him.”

When Johnson came to power Seldon hoped the programme might continue – Johnson did after all have a lucrative contract to write a book about Shakespeare. There was no interest whatsoever. “Covid made things difficult obviously,” he says, “but we did come in. Johnson never once showed up. As [his school reports showed] he had no deep interest in any classical history, language or literature or Shakespeare. His examples were always for show. At his heart, he is extraordinarily empty. He can’t keep faithful to any idea, any person, any wife.”

The tragedy of that fact was twofold, Seldon argues. For one thing Johnson was a non-starter as a competent prime minister, let alone a great one. The historian numbers nine out of 57 in that latter category (Attlee and Thatcher are the two who make the cut postwar). “The great prime ministers are all there at moments of great historical importance,” he says. “But they have to respond to them well. Chamberlain didn’t; Churchill in 1940, did. Asquith didn’t; Lloyd George did in 1916. Johnson had Brexit, he had the pandemic, he had the invasion of Ukraine and incipient third world war. He could have been the prime minister he craved to be, but he wasn’t, because of his utter inability to learn.”

We saw some fear of some of the people around Gordon Brown, but this was off the scale. And that’s a deeply unhealthy facet of modern government

The related tragedy was the national one, in which we are still living. Whatever you thought of Brexit, Seldon argues – he thought it was a bad idea – it did provide “the overdue opportunity to modernise the British state and Britain’s institutions. There was a desperate need to bring the civil service up to date,” he says. “To forge better connections between universities and public life, to rejuvenate professions.”

But of course the adolescent “disruptors” that Johnson was amused and supported by had no interest in that work. Their goal was either personal enrichment or, in Cummings’s case, the application of that Silicon Valley mantra “to move fast and break things”. Disruptive change can work in the commercial sector because you are replacing one product or technology with another in a limited market. One lesson of Seldon’s book is that to apply that idea to government is a fundamental misunderstanding of what government is. Degrading and destroying institutions is not the way to reform them.

“People we spoke to were afraid of Cummings, personal fear,” he says. “And to an extent of the whole Johnson court. In the seven books I’ve written, we saw some fear of some of the people around Gordon Brown, but this was off the scale. And that’s a deeply unhealthy facet of modern government that you let in people who are using fear as a method of control. Quite a lot of that was misogynistic in what we saw.”

In another of his roles, Seldon has been tasked with examining how institutional competence and trust might be re-established. He has recently become deputy chair of something called the Commission on the Centre of Government, created by the Institute for Government, which will recommend steps to improve the workings of the Cabinet Office and No 10, post-pandemic and Brexit and Johnson and Cummings.

“The fact is,” he says, “people come into No 10 knowing less about [complex organisations] than most people running companies employing less than 20 people. That’s forgivable. What is unforgivable is that almost without exception, they do not want to learn how to do it. They think they know best. They are often snide, poisonous, dismissive of previous teams, particularly teams from their same party. And they come in with frothing adrenaline and swagger.”

If Johnson was the blueprint of that failing, his immediate successor, prime minister Liz Truss, was a kind of cringeworthy caricature of hubris (Seldon will write about her costly tenure as a £65bn preface to the arrival of Sunak). Given these examples is he optimistic that confidence in government can be rebuilt?

“I think that Johnson and Cummings were what was needed to bring the country to its senses,” he suggests. “People didn’t want things broken up. They wanted to be listened to. They wanted institutions that were more relevant to them. They felt excluded by metropolitan elite. Nobody is happy with what has happened.”

We can agree on that much, I suggest. But does he really think that the lessons of Johnson’s government have been learned?

“If Johnson understood more about classical philosophy, he’d have recognised that an antithesis – being against something – isn’t enough. The country now needs a synthesis from whichever party. The great prime ministers are healers and teachers. They need to be able to tell a story of where they have come from and to where they will lead us.”

Is that leader evident to him?

“Well,” he says, “this is the reason why for the moment Starmer is disappointing, because there is this enormous desire for renewal. But Starmer seems micro when he could be macro, cautious when he could be passionate, dull where he could be inspirational.”

He doesn’t make it sound like much of a page-turner, I say. But having read the current volume, I’ll still be looking forward to that particular sequel.

-

- Johnson at 10 by Anthony Seldon and Raymond Newell is published by Atlantic (£25). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply