[This is a chapter from Tim’s Crook’s book on International Radio Journalism, published by Routledge and available from January 1998]

This is an uncharted and neglected area of research in radio and the chasm needs to be filled. The political and cultural block on alternative radio news in the UK from 1922 to 1973 was unjustifiable and represents a form of economic and political censorship. Close analysis of Royal Commissions and Parliamentary committees of enquiry into broadcasting suggest that competitive motives were responsible for the lack of progress. The newspaper interests in Britain feared a drain on the existing scale of advertising. A public sector broadcasting system funded by tax was a limited threat. The BBC became a very powerful lobby and its parliamentary influence cannot be underestimated.

Scientific ignorance also played a part. Politicians were persuaded that the spectrum for radio broadcasting was finite, although now it is difficult to understand how BBC engineers could sustain the argument that BBC transmission waves were so large that there was no room for anyone else. Ignorance and prejudice against foreign commercial radio environments played into the hands of those lobbying against commercial competition.

This began to be dispelled when the world became smaller through international communications and jet travel for business and tourism. The vested interests militating against commercial radio licensing sustained their hegemony from 1955 to 1973 even when ITV and Independent Television News successfully developed an international reputation and challenged BBC TV news in terms of style and audiences. The BBC was fortunate in that the Labour Party during the 1960s and 1970s had a political policy opposed to commercial radio. The BBC was also fortunate that the explosion of pirate radio during the 1960s, stimulated by the huge blossoming of youth culture and popular music had been manipulated by newspapers and political parties into a ‘moral panic’. New legislation introduced to the House of Commons in 1967 by Labour Post Master-General Anthony Wedgwood Benn effectively outlawed pirate broadcasting and the BBC was given the task of responding to the needs of youth culture by transforming its broadcasting networks to meet popular demand. Radio One was the result. Most of the new station’s disc jockeys had been recruited from the legally harassed and economically disabled pirate services. Unlike Labour, the Conservative Party was committed to the idea of a competitive market in radio and towards the end of the 1960s former athlete, Christopher Chattaway MP, was at the centre of a successful campaign to introduce new legislation licensing independent radio.

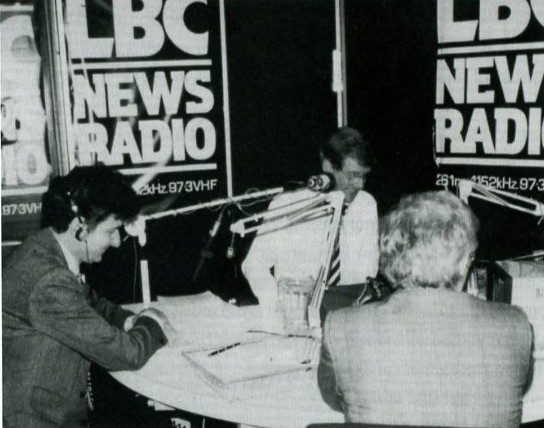

There was a deliberate plan to begin with an all news radio service modelled on the New York radio station WINS. The Conservative government under Prime Minister Edward Heath between 1970 and 1974 provided the window of political opportunity. The London Broadcasting Company started its service at 6 am on October 8th 1973 with audio birthday cards from leading politicians including Labour leader Harold Wilson who reaffirmed his party’s opposition, but welcomed the radio equivalent of ITN. UK radio had reached the point of no return and BBC radio journalism had to face up to a force of competition which would profoundly change its news gathering and broadcasting culture over the next twenty years.

LBC and UK independent radio’s national and international news service, IRN, have pioneered developments in both the technology as well as the style of radio journalism. Many of these developments have been borrowed from well established traditions in America and Australia. The organisations were sited in the middle of London’s Fleet Street newspaper community. Their broadcast journalists were a stone’s throw from pubs, restaurants and meeting places frequented by the country’s leading national newspaper journalists. This enabled LBC and IRN to have a much more independent journalistic culture and news priority agenda. The sequential nature of commercial broadcasting meant that the station’s schedule was much more flexible in accommodating news gathering and broadcasting responses to dramatic and changing events.

The introduction of talkback phone-in radio brought the journalists in direct communication with listeners who were allowed to articulate opinions, views and provide direct information. In the beginning IRN only had one member of staff, Fred Hunter, who had been recruited from the government’s information service, the COI. IRN’s development depended on the further licensing of local commercial stations who had to pay a subscription fee based on audience size, turnover and profits. The first major story was the Yom Kippur war between Israel and its neighbouring Arab countries. IRN’s first news bulletin was presented by Australian radio journalist Ken Guy. The first words of the bulletin were in a popular direct style: ‘The Middle East War’. The writing was short, simple and concrete. The first report was an ad-libbed actuality based ‘voicer’ from UPI radio correspondent, Richard C Groce, in Northern Israel. You could hear the rumble of tanks driving towards the Golan Heights as he talked into his microphone:

‘Here comes another one I think. And this one has its gun facing forwards. Two men staring out the top turret. This main street actually in more normal times is like a main street anywhere. Traffic here is tanks, armoured half tracks, command vehicles and jeeps, the stuff of any army on the move. That’s because this town is hard by the frontier with the occupied Golan Heights. Here comes another tank…tank commander gave a wave. The troops and vehicles have been moving through this town on the way to the front since Israel first started mobilizing its troops on the first day of the war. If I turn around I can see pops of white smoke on the hills on this side of the heights that face Israel proper. And from there are dulled explosions that one can hear from time to time. The soldiers here have been mobilized hastily and some of them are still wearing dungarees, civilian shirts, or teeshirts and they’re either going to change into uniform away to the front or else go fight in their dungarees. Traffic here is heavy, the heaviest it has been since the last war in 1967. One soldier told me ‘This time it is going to be the last one’. This is Richard C Groce at a small town in Northern Israel near the occupied Golan Heights of Syria’.

LBC and IRN relearned the basics of radio journalism by changing the outmoded and bureaucratic practices of reporters who had been recruited from the BBC and importing the skills of mainly Australian and New Zealand itinerant radio journalists who were on their ‘world trips’. An influential figure was John Herbert who had been in the thick of ABC’s battles with Gough Whitlam’s Australian Labour government in 1972, had worked at editorial level at the BBC World Service and later wrote the first book on radio journalism which averred to practice outside the BBC. There is an apocryphal story that LBC were at one point so desperate for experienced freelances that an editor was despatched to the Aldwych which was a traditional gathering point for international travellers from ‘down under’. Here travellers sold their camper vans on to compatriots wishing to take on the world tour via Katmandu. The story goes that the editor had to move from camper van to camper van saying ‘Anyone here a radio journalist from Australia or New Zealand?’

In the next twenty to thirty years IRN/LBC became a substantial training ground for broadcast journalists who now figure prominently as international bi-media correspondents and programming executives. Generations of reporters learned their trade in reporting London news events and many journalists in their early twenties found themselves flying around the world with a battered Marantz cassette recorder, ‘Comrex’ telephone transmission enhancement unit and a personal credit card which would eventually be reimbursed by the station’s expenses accountant Tony Darkins. Years later he would be recruited by News Direct 97.3fm as a producer for rolling news format programmes. The lively, ambitious and enthusiastic community of journalists walking in and out of the basement headquarters in Gough Square changed the face of UK radio journalism. The most influential editors and managing directors included former ITN reporter George Ffitch, former Daily Sketch and Daily Telegraph journalist Peter Thornton, Keith Belcher, Ron Onions, Linda Gage, Dave Wilsworth, and John Perkins. There were many others in the chain of editorial command who determined the style and content of the news coverage including bulletin editors, intake editors and network editors such as John Greenwood, Jim Keltz, Derek Grant, Rick Thomas, Nigel Charters, Colin Parkes, Robin Malcolm, Charles Morrissey, Vince McGarry, Chris Shaw, Charlie Rose, Vivienne Fowles, Kevin Murphy, Stephen Gardiner, John Sutton, and Marie Adams. I can only apologise for omitting the names of many other journalists who made a significant contribution during this period.

Up until 1987, IRN’s resources had expanded with the subscription fees provided by the burgeoning ILR network of stations and this had been combined with a subsidy from the sister company LBC. The operation was labour intensive, but despite fluctuations in funding and the threat of redundancies in four to five year cycles, LBC was a remarkable success. The station was protected by a limited radio market. For many years there were only two commercial stations in London and the competition was music format in the form of Capital Radio. UK spending on radio advertising remained stubbornly restricted to two per cent. The introduction of ‘Newslink’ with a spectacular presentation on the Orient Express radically changed IRN’s funding base. Newslink was the UK’s first national radio network advertising opportunity. The IRN morning bulletins would include commercials and the revenue earned from this selling point meant that IRN carriers would no longer have to pay subscription fees. Soon IRN’s commercial prowess would result in carrier stations receiving a Newslink dividend. Previous IRN subscribers became significant shareholders and IRN was no longer a financial subsidiary of LBC.

A former IRN/LBC industrial correspondent and negotiator for the National Union of Journalists, John Perkins, successfully steered IRN to commercial success and domination of the news provider market through the late eighties and nineties. Many attempts were made to challenge the IRN hegemony. They included expensive loss-leader news services from Network News, ITN and Reuters, but these were unsuccessful. IRN contracted out the service provision to ITN in 1991 after a major decline in LBC’s fortunes. In 1989 LBC’s new owners Crown Communications made a series of poor management decisions which included leaving Gough Square, changing the identity of the station by launching two new services on the AM and FM frequencies and failing to match expenditure with income. By the time the Radio Authority withdrew the licence in 1993, IRN had found a new home in the highly resourced multimedia ITN building in Grays Inn Road. LBC returned to the London radio scene with another change of ownership in 1996 and the sensible decision to return to the original branding. It is ironic that the LBC of the present day is again operating on the same floor as IRN and its sister FM station News Direct 97.3fm.

Although it is an analysis born of nostalgia, it is quite clear that maintaining the pre-1987 economies of scale at Gough Square and a continuity of radio journalism culture would have preserved LBC’s unique position of qualitative news and current affairs based broadcasting which had been the envy of the BBC. From 1987 successive managements failed to appreciate the value of audience loyalty and brand identity of a 20 year track record in broadcasting, overestimated the threat of an expanding radio market and underestimated the expansion in advertising expenditure. Another catastrophic mistake included relocating to an inaccessible suburb of London in an expensive leasehold office block which became a white elephant when property prices in the City collapsed shortly after the move. LBC/IRN could have remained in Gough Square with a peppercorn rent and would have been adjacent to powerful decision making centres of finance, politics and law. The history serves to show how a vibrant and creative centre of journalism culture can be undermined by a series of organisational failures in a liberal democracy and capitalist economy that allows business takeovers and the buying and selling of media assets. The ‘regulation’ by the old IBA and succeeding Radio Authority is open to question. Should the IBA have permitted the Australian media entrepreneur David Haynes to buy LBC/IRN from the Canadian conglomerate Selkirk Communications in 1987? Should the unelected Radio Authority have been allowed to withdraw LBC’s licence in 1993 when the station had successfully recovered from its earlier losses and had re-established its share in a more competitive London radio market? Politics may have been influential in a highly unpopular decision. The station’s owners Chelverton Investments were inextricably linked to former Westminster Council leader Dame Shirley Porter who was being accused by the District Auditor of selling council homes to buy Conservative votes. The Radio Authority awarded the franchise to the group led by LBC’s former Managing Director, Peter Thornton. But Peter Thornton’s group did not have the necessary financial base to launch the new services and had to sell out to Reuters which had been a rival franchise bidder. These events undermined the credibility of regulation and leave uncomfortable question marks over whether the politics of broadcasting were more important than the merit of broadcasting operations. Many of these questions are difficult to answer because the Radio Authority conducted its decision making in secret and was not obliged to provide any reasons for its decisions.

IRN/LBC reporters demonstrated a faster response to news events from 1973 onwards. Sometimes reporters as a result of receiving tip-offs from freelances monitoring emergency service frequencies, or telephone calls from listeners, would be on the scene of major crimes before the police. There was one celebrated occasion when an LBC reporter conducted an interview with the victims of an armed robbery. They had been locked inside their warehouse. As questions were asked and answered through the letterbox police sirens could be heard getting closer and closer. Another reporter conducted a bizarre interview with an anti-immigration National Front supporter while he was fighting with an Anti-Nazi League protester. Interviews with Captain Mark Phillips and Princess Anne prior to their wedding in 1973 betray sexist cultural values of the period. Princess Anne is asked if she would make a good housewife, and would she cook her husband’s breakfast before he goes off to work? She was also asked if she could sew on a button. She replied with considerable equanimity that she had been quite well educated.

The IRA’s mainland terrorist campaign from 1973 onwards produced dynamic and disturbing actuality reports from reporters Ed Boyle and Jon Snow. News packages are produced with ad-libbed links mixed with the actuality sound of interviews and location recordings. Ed Boyle arrived on the scene of the pub bombing in Guildford shortly after the fatal explosion. His language is imagistic and direct: ‘The quaint shopping streets littered with broken glass, footprints in blood outside a clothing store, people crying, policemen everywhere, Guildford has never seen and never wants to see again anything like it’.

Ed Boyle became IRN/LBC’s political editor by 1975 and on Monday June 9th of that year commentated on the first broadcast from the House of Commons. In that year Jon Snow became the first radio reporter to use a radio car phone to broadcast the end of a dramatic siege of an IRA active service unit that had been cornered in a flat in London’s Balcombe Street. The four men who gave themselves up adamantly indicated that they had been responsible for the pub bombings at Woolwich and Guildford, but the British judicial system continued to detain eleven people who became known as the Guildford Four and Maguire Seven for crimes they had plainly not been responsible for. LBC interrupted its regular schedule to take this live report from Jon Snow who was well known for travelling to the scene of London news stories on a racing bicycle:

‘The four gunmen have come out. The siege here has just ended one minute ago. There is still a great deal of activity here, but a blue flashing lighted van has just swept off into the distance with its siren wailing. Briefly a figure came out onto the balcony, looked over, went back in again. Another came out, looked over, went back in again, and then suddenly we saw the four being led across the street into the police van and away they’ve been swept. There is still a very heavily armed presence all round. I am just getting further information. Just one moment’. ANOTHER JOURNALIST SAYS ‘THAT’S A GUNMAN WITH A WHITE HANDKERCHIEF’. ‘A gunman with a white handkerchief has literally just come out. Really it is so dark up that end now. We are obviously going to have to wait for the firm confirmation of the police but the evidence so far is that we are right at the very end of this siege’.

IRN’s parliamentary unit covered the major political events of these two decades and in particular the rise to power and triumphant general elections of Mrs Margaret Thatcher. Ed Boyle was succeeded as political editor by Peter Allen who successfully drew out of this politician views and opinions about sound domestic housekeeping which were to become the cornerstones of ‘economic Thatcherism’. Peter Allen left IRN to pursue a successful career as a television political specialist and is now co-presenting the successful breakfast programme on BBC Radio Five Live which is drawing listeners away from the Radio Four flagship ‘Today’. He was succeeded as IRN’s political editor by Peter Murphy who is admired for his wit and ability to focus on the real news value of political developments.

In 1975, LBC reporter Julian Manyon travelled to Saigon to witness the fall of the South Vietnamese regime to the Vietcong and North Vietnamese army. He stayed behind after the frantic evacuation of the American embassy by Chinook helicopters. He produced a remarkable five minute long ad-libbed telephone account of Vietnam’s fusion into one country. It combined dramatic, concrete description with assured analysis of the significance of what he had seen. Here is an example:

‘Whatever one’s political views about the rights and wrongs of the war what is undisputed is that the North Vietnamese and Vietcong soldiers were far better disciplined, far better controlled and just basically obeyed orders’.

In 1980 IRN/LBC journalists were broadcasting live on the dramatic end to the Iranian embassy siege. It was a sunny Sunday afternoon when the British Home Secretary gave his permission for the SAS to attack the building. By this time Iranian separatists had begun to shoot hostages and dump their bodies on the steps outside. The first to die was the Iranian press attaché. BBC personnel had been inside the building when the siege began. Producer Chris Cramer had been allowed to leave after being taken seriously ill. A duty BBC television reporter, Kate Adie, was also present with the IRN reporting team of Malcolm Brabant and Peter Deeley.

The journalists there were clearly shaken and shocked by the blasts of percussion grenades, the outbreak of firing and an enveloping fire. Kate Adie has been criticised for screaming when the firing began, but she has rather pointedly observed that her friends and colleagues were inside the building as hostages and she feared that they were being murdered. Her accomplished live reporting of the event for BBC television brought her to the notice of editors and in the following years she became the BBC’s Chief News Correspondent and Britain’s most popular broadcast journalist. It is a salutary tribute to radio journalism that she learned her trade as a radio reporter for seven years in local BBC stations. The young Malcolm Brabant was challenged by the struggle of having to provide accurate and live eye witness description to LBC listeners while being completely unaware that SAS soldiers were entering the building in a ruthless military operation which would result in the deaths of all but one of the gunmen. His ability to keep his head under fire stayed with him through the rest of his career which has included award-winning reporting of the war in former Yugoslavia.

Like America in the 1960s, Britain in the 1980s was to witness severe outbreaks of public disorder caused by decades of economic deprivation, racial prejudice and aggressive police tactics in Asian and Afro-Caribbean communities. Youths attacked police officers with petrol bombs, and business premises were looted. IRN/LBC, like every other area of the media, was poorly represented by non white journalists. IRN reporter Paul Davies witnessed the first petrol bombs being thrown at poorly protected police officers at Toxteth in his native Merseyside:

SHOUTING AND BEATING OF BATONS ON SHIELDS. ‘And the noise that you can hear now is the police beating on their riot shields as they move into a barrier in the centre of the road. They are coming under fire now. Missiles. There’s a large crowd of youngsters at the other end of the street. They seem to have got hold of a civilian car. They’ve turned the person out of it and they’re pushing it towards the direction of the police barricade. The police are moving up the street and they’re coming under heavy fire. They’re now forming what looks rather like the old Roman system of using their riot shields to protect not only their sides, but also their heads. And bottles are coming in. One just landed very near to me and a stone just there. The police are having to duck for cover beneath their riot shields. The stones really are flying in. Some of the youths, their faces hidden by scarves and masks. That car that was just taken has been crashed into some railings and the police are now moving in again, beating their riot shields and trying to break up a crowd of youths who are now sprinting back up the street, still throwing bottles, and bricks at the police…SHOUTING, CRIES AND SMASHING GLASS. And there goes the first petrol bomb that I have seen. It came flying over the ranks of the policemen. Burst into fire. Nobody seems hurt at this moment. Policemen putting it out with a fire extinguisher. But there comes another one. A bottle straight into the ranks of the policemen. The crowd screaming as that Molotov cocktail burst into flames’.

By the early 1980s IRN/LBC had developed a comprehensive team of staff reporters, correspondents and specialist freelances who could make a decent living on retainers and piece work deals with editors. This meant the services could benefit from the first broadcast legal affairs team covering the Royal Courts of Justice and Central Criminal Court day by day. After 1983, I was concentrating on Old Bailey trials and cases heard outside London. My colleague Tim Knight covered civil hearings and appeal court cases at the RCJ. The BBC duplicated specialist resources in legal affairs several years later.

LBC’s local government correspondent Jo Andrews provided live links from County Hall opposite the House of Commons on the controversial reign of left wing GLC Labour Leader Ken Livingstone. Notable freelance specialists included diplomatic correspondent David Spanier and defence correspondent Paul Maurice. Andrew Manderstam covered the USA in Washington DC. IRN staff reporters covering world events during the 1980s included Barbara Groom, Andrew Simmonds, Margaret Gilmore, Chris Mann, Mark Mardell, Lindsay Taylor, Michael O’Neill, David Loyn, Antonia Higgs, John Draper, and a young journalist recruited from the Birmingham ILR station, BRMB – Kim Sabido who found himself despatched on a naval task force to cover the Falklands War in 1982.

The Falklands War demonstrated that LBC/IRN could cover a national emergency as well as any other news organisation. The BBC, in particular, became disturbed that in the Greater London area, listeners turned to LBC because it maintained sequential news and current affairs programming twenty four hours a day and would interrupt light programme, entertainment slots for important developments. BBC Radio Four found that the structured tradition of block programming prevented news flashes being broadcast in the middle of pre-recorded one and a half hour plays. During the Gulf War, the BBC responded by turning its national FM frequency over to a concentrated news and current affairs service concentrating on that war’s coverage.

The Ministry of Defence excluded all foreign journalists from accompanying the naval Task Force sailing to the Falklands. The four broadcast specialists, Robert Fox for BBC radio, Brian Hanrahan for BBC television, Kim Sabido for IRN, and Michael Nicholson for ITN worked on a pool basis. During the events all the reporting was radio. Television pictures were not allowed out until after the islands had been recaptured. The only woman broadcast journalist covering the war was IRN’s Antonia Higgs who reported the Argentine side in Buenos Aires. This tough, resourceful general reporter was also the first British broadcast journalist to land on the Caribbean island of Grenada after the US invasion by marines.

Kim Sabido’s journalism during the Falklands War was in the best tradition of war reporting – honest, vivid, sensitive, and informative. He decided to join the troops ‘yomping’ through the marshy peat bogs to do battle in the mountains behind Port Stanley:

GUNFIRE. ‘You can hear now the bullets whizzing around us. Ricocheting off the rocks. A heavy salvo of small arms fire, machine gun fire coming both down the hill and then up the hill in reply from the British troops ahead of me. GUNFIRE AND EXPLOSIONS. More incoming gunfire. From Argentine batteries around Stanley. Keeping everybody’s heads down. CRIES AND SHOUTING. Somebody’s been hit up front. LOUD EXPLOSION AND CRACK OF SHRAPNEL AGAINST ROCK. Good Heavens! Everything now landing far too close for comfort. I just heard somebody up front about twenty or thirty feet has received a bullet in the leg or something.’

In one of the despatches he sent, Kim Sabido made the poignant observation: ‘I can honestly say that my thirst for action, if that is what it was, has been fully satisfied. I pray earnestly I shall never have to face another night like that again. And I can assure you that there are many more young men here who share that sentiment’.

IRN’s Andrew Simmonds was recovering from a back operation during the Falklands War. Although frustrated by missing the opportunity of reporting such an important news event, he was to have no shortage of drama as IRN’s reporter in Beirut during the Israeli invasion of Lebanon. After checking in at his hotel, he went out with colleagues and returned later to find it had been reduced to a pile of rubble. The Israeli bombardment created human suffering on a vast scale. At one point he simply decided to describe events into the microphone as a mother wailed with uncontrollable grief:

‘You can hear the screaming of a mother who believes her child is underneath the huge piece of concrete. I can’t really describe in any acceptable tone what I can see now. THE SOUND OF DIGGING WITH SPADES AND THE ENGINE OF EARTH MOVING MACHINERY. There is the body of a man underneath the massive slab of concrete – only a leg showing. There can be no hope for rescuing this man. But the mother insists she heard the screams of her child underneath all of this and so the bulldozer moves forward and relief workers crowd around what really can’t be anything else but a massive hideous concrete graveyard. SCREAMING VOICE OF BEREAVED MOTHER. SIREN OF AMBULANCE BLOCKED BY THE BULLDOZER DRIVING BACKWARDS AND FORWARDS.

As world news events broke throughout the 80s and 90s, IRN reporters were present to provide a fresh, popular approach to radio journalism. Dave Loyn’s reporting of Indira Ghandi’s assassination won him the Sony Reporter of the Year in 1985. Lindsay Taylor’s reporting of the Kings Cross fire also earned him the same accolade in 1988. In one year the Sony judges refused to make an award because there had been no IRN/LBC entries and they were not satisfied with the standard offered by BBC radio reporters. However, this golden period of independent radio reporting seems to have passed. The journalistic infrastructure that served both IRN and LBC was broken up through aggressive management policies in the early 1990s. Key journalists took voluntary redundancy or found alternative employment in other broadcast services. The transfer of IRN personnel to ITN’s managed service saw further reductions in staffing levels and experience.

Network stations no longer demanded 30- to 40-second voice reports and wraps which used the medium skilfully. The demand in the late 90s has been characterised by short cuts of actuality, and two minute bulletins written in a predominantly tabloid newspaper style. The editing of the service by its first woman editor Derval Fitzsimons required a more complex balance of resources to provide different outlets to a larger and more demanding market. Access to ITN’s reporters and international news bureau created a bi-media service which meant that expensive international connections could be achieved by interviewing and asking for reports from television reporters, many of whom used to be IRN reporters. Derval has shown that she is more than up to the task. IRN recently won the contract to provide news to British Forces Broadcasting from the BBC.

There is every sign that IRN continues to be in the front line of award-winning coverage. In 1996 Andrew Bomford’s documentary on the trial of serial killer Rosemary West won a gold medal at the International Radio Festival of New York and twenty one years after his report on the fall of Saigon, Julian Manyon’s radio reporting of the Chechen war with Russia was also recognised at the 1996 Festival. In recent years independent radio has vied with the BBC in the battle to command the majority share of radio listening in the UK. IRN continues to be a powerful competitor, but the BBC has responded with substantial investment in news and current affairs since 1987. BBC radio reporters have more outlets and greater capacity for varied coverage of news events. The all news and sport network, Radio Five Live, staffed by many former LBC/IRN journalists, continues to enjoy substantial increases in listening figures.

The depth of IRN radio news coverage may be limited by the fact that News Direct 97.3 fm is only a London service and Classic FM’s Six o’clock ‘Classic Report’ is the only opportunity for a national platform for independent radio reporting.

The death of Diana, Princess of Wales, on August 31st 1997 and the subsequent funeral demonstrated that LBC, News Direct, and IRN were more than up to the task of responding appropriately. LBC, in particular, surpassed all BBC national networks by abandoning normal programming into a responsible and sensitive news reaction and analysis service between 1 am and 6.15 am. As overnight presenter, I used the World Wide Web, Press Association, IRN and News Direct sources to guide the growing audiences of London listeners through a traumatic morning. Internet news groups and other radio analysts have now acknowledged that LBC was the first UK radio station to transmit ‘reports of her death’ and became the first UK broadcaster to confirm her death. The entire broadcast for five and a half hours was unscripted and is currently being examined and analysed by a team of sociologists who wish to explore the subject of broadcast news communication and public mourning. LBC received a deluge of letters from listeners who wanted to appreciate that LBC had found the the right tone and the right approach.

The success of the LBC and News Direct operation owes much to the professionalism of programme editors Charles Golding and Chris Mann who arrived at the ITN building within half an hour of the first report of the serious road traffic accident in Paris to direct editorial management of the story. News Direct’s rolling format news coverage throughout that day and the subsequent week drew plaudits from all sides of the industry and a special letter of recognition from Janet Lee, the Deputy Head of Radio Programming at the UK Radio Authority. IRN’s coverage was equally impressive. The independent broadcasters seemed to be more in tune with the mood of public opinion and showed greater flexibility than their BBC counterparts who found themselves hidebound by programming rules and bureaucracy.

Updated/maj. 06-04-2019

Vues : 1