Article by Eric Berger in Ars Technica on 9/6/2022.

“We cannot work with a partner who is completely trampling on those values.”

Half a year after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the implications of this war for the European space industry have been profound. Most notably, Europe has severed all connections with the Russian launch industry and canceled a joint mission to place a European rover on Mars with the help of a Russian rocket and lander.

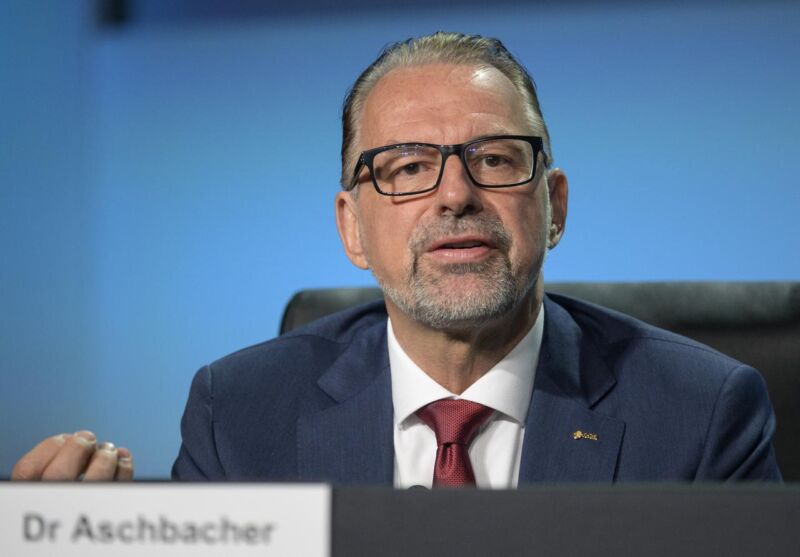

The process of unwinding the deep links between Europe’s space program and the Russian space industry have fallen largely on the shoulders of an Austrian space researcher named Josef Aschbacher, who had been director general of the European Space Agency for less than a year when Russia’s tanks began rolling into Ukraine.

Like most Europeans, he was aghast at what he saw. “Look at what is happening on the ground,” he said in an interview with Ars. “I’m really disgusted by the invasion of Ukraine. We see it every single day. What is happening there is not meeting our European values, and we cannot work with a partner who is completely trampling on those values.”

Soon after the Russian invasion, relations between the two space programs broke down. Russian workers at Europe’s main spaceport in French Guiana walked off the job and returned home. A launch of OneWeb satellites on a Russian rocket, brokered by the European Space Agency, was scrubbed. Those 36 satellites remain stranded in Kazakhstan, and OneWeb recently took a $229 million writedown.

Prior to the war, Europe had relied on Russia’s Soyuz rocket for its medium-lift needs—for payloads larger than its Vega rocket could accommodate but not large enough to necessitate the more expensive Ariane 5 rocket. That partnership had been expected to continue even as Europe brought a new generation of rockets, the Vega-C and Ariane 6, into service. But no longer.

“I cannot see a rebuild of the cooperation we had in the past,” Aschbacher said. “I am speaking here on behalf of my member states. They all have very much the same opinion. And this is really something where the behavior of ESA will reflect the geopolitical situation of the member states on this point. And I think this is very clear.”

This schism has left Europe with a short-term challenge, however. It had planned five Soyuz launches in 2022 and 2023 to carry European payloads into orbit. Because the new Ariane 6 rocket will not be ready to enter service until at least next year, Aschbacher has had to look for alternatives, including the continent’s rival for commercial launches, US-based SpaceX.

“You have to see it from a very unemotional and business point of view,” he said. “We had five launches foreseen on Soyuz, and they have been scrapped. Right now I’m in contact with different operators. SpaceX is one of them, but also Japan, India, and basically we want to see whether in principle, our satellites can be launched on their rockets. Sometimes there’s a lot of emotion put into this. This is, for me, a very practical management decision. There is no financial offer on the table. We have just technically explored whether this is possible, but the exercise is still ongoing.”

Ironically, it was an act by NASA that fostered deeper cooperation between the European Space Agency and Russia. In 2012, to help pay for cost overruns on the James Webb Space Telescope, NASA canceled its participation in the ExoMars mission that sought to land a European spacecraft on Mars for the first time. In the wake of this decision, Europe turned to Russia, which became a full partner in providing a Proton rocket and a landing module.

Now, a decade later, ESA and NASA are discussing working together on ExoMars again. Given the political climate today, NASA has been far more amenable to helping get Europe’s rover, named Rosalind Franklin, safely down on the surface of Mars.

Aschbacher was in Florida earlier this month for the Artemis I launch. Despite the tensions with Russia, he was bullish about the future and Europe’s partnership with NASA, which seems stronger than ever. As part of NASA’s Artemis program, Europe is building a Service Module for the Orion spacecraft, which is critical to providing power and propulsion to the capsule where astronauts reside. This partnership will likely extend to the surface of the Moon and should see European astronauts landing on the Moon later this decade.

“Being a critical element of this mission is important,” Aschbacher said. “The European Service Module is on the critical path, and without it, astronauts cannot be brought to the Moon and back. That’s huge. During Apollo, there was only the US and only the USSR. Europe was watching from the sides, and of course being fascinated, but not involved directly. Today is historic for America, of course, but it is even more historic for Europe because we are a part of it.”

Updated/maj. 09-09-2022

Vues : 2