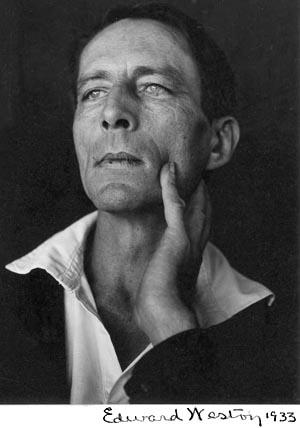

In 1923 at the urging of his friend Roubaix de l’Abrie Richey and their shared lover Tina Modotti, Edward Weston left his family and moved to Mexico where he embarked on a new chapter in his career that would prove influential in directing the course of his photography. Whereas his earlier portraits adhere to many of the classic characteristics of 19th century portraiture- stoic poses, elaborate costumes, accessories reflective of the sitter- his Mexican period, as seen in lots 254, 255 and 257, illustrates his interest in incorporating elements of Modernism and experimenting with alternate methods and approaches to portraiture.

In his first portraits in Mexico, Weston abandoned the studio setting and photographed his sitters against the backdrop of an overcast sky. Tightly cropping the images so that their faces dominated the full frame and shooting from a lower vantage point, gave the sitters a weight and monumentality atypical of the classic portrait. Collectively, Weston had come to refer to that body of work as “heads.” The Mexican writer Francisco Monterde Garcia Icazbalceta perceptively described them as “guillotine heads in the noon sun: unreal necks and martyred eyes in harsh, insolent light.” (Conger, n.p. fig 110/1923) By isolating the head from all context, Weston was able to capture uniquely intimate moments, ones that speak to, not only the disposition of the sitters, but even more to Weston’s personal relationships with them.

When Weston met Diego Rivera at his first exhibition in Mexico in the fall of 1923, Rivera quickly became a champion of his work, drawn to the Modernist elements echoed in his own works.The two became close friends and Weston would go on to photograph both Rivera and his wife Guadalupe Marin de Rivera during his two years in Mexico. In Diego Rivera, Mexico, 1924 (Lot 255) one can see the admiration and respect that Weston had for his new friend; that Rivera looks down upon Weston with a jovial expression and Weston, in turn, literally looks up to Rivera, suggests a rapport reminiscent of a mentor with his mentee. Similarly, in Guadalupe Marin de Rivera, 1923 (Lot 257) Weston captures her mid-speech with her mouth agape. From Weston’s own writings of Guadalupe, this is perhaps the most appropriate manner for him to depict her as he wrote of his affection for her “strong voice, almost course, dominating.”

But neither of these “heads” are quite as revealing as Tina with Tear, 1923 (Lot 254), which shows Modotti with a tear rolling down her cheek. The act of photographing someone, by its very nature, is an intimate act, but to do as that someone expresses vulnerability supposes an undeniable trust between the photographer and sitter. While Weston’s nudes of Modotti are far more intimate in a literal way, their chief concern lies within the formal qualities of her body. Here, by contrast, the camera nearly becomes transparent as we see Modotti not through a lens but through the adoring eye of her lover.

In as much as Weston’s “heads” demonstrate his fascination with contemporary icons of Mexican art, such as Rivera and his wife, he was equally interested in the greater history of Mexican culture. In Cholula Costume (lot 256), Weston portrays the dancer and choreographer Rosa Covarrubias in native Mexican attire. In 1930 Rosa married Miguel Covarrubias, the renowned Mexican ethnologist, art historian, painter, caricaturist, and set and costume designer. Rosa and Miguel were close friends of Weston and Modotti, who taught Rosa photography. What Weston captured in his lens is not merely the “woman of great beauty and charm” as described by José Limón in his biography, but also a model of traditional Mexican culture, one that was researched and consequently introduced by Rosa and her husband to create a new era in contemporary Mexican dance.

Updated/maj. 03-02-2022

Vues : 23