Article by Chris Day dated June 2016 based on the book “Peta, the official Home Office cat”

Since the 1800s there has been a group of government employees who have been given free range over Whitehall, allowed to stroll into Ministers’ offices during the most sensitive of conversations. They’ve been paid out of the public purse to preen, sleep and hunt in the corridors of power.

They are the government’s cats.

The government has been unofficially ‘employing’ cats since the mid 19th century – not as a forward thinking precursor of today’s therapy dogs – but for the far more gruesome task of ridding Westminster of mice and rats.

The practice of government departments having cats continues today. Keen-eyed viewers of news reports outside 10 Downing Street might spy the slinking figure of Larry, Chief Mouser to the Cabinet Office, in the background.

Larry, Chief Mouser to the Cabinet Office (image from Wikipedia)

Meanwhile the Foreign Office has recently appointed the rescue cat Palmerston as its Chief Mouser; he has already gained a substantial following on Twitter.

Most of these mousers have been unofficial, and left no paper trail. However, records were created when departments applied to the Treasury for a feline upkeep allowance, making these cats official. Details of some of them are preserved in The National Archives.

In 1936 for instance, the Cabinet Office applied for an allowance for their resident mouser, Jumbo. Jumbo died in 1942, his name forever ‘recorded in our CAT-alogue of Events during the war’. In light of the need for men at the front, it was suggested by one Cabinet wag that his replacement be a female feline (catalogue reference: CAB 150/7).

The official Home Office cat

It is the Home Office who kept the most meticulous record of their feline employees, and their exploits are detailed in The National Archives’ file HO 223/43.

It all began in 1929, when the Treasury agreed to 1d (one pence) a day being spent on the upkeep of Peter, a black cat already resident in the Home Office. The upkeep was not applied for because Peter was underfed, the Home Office said, but quite the opposite – titbits brought in by besotted civil servants had led to Peter neglecting his main duty as the office mouser.

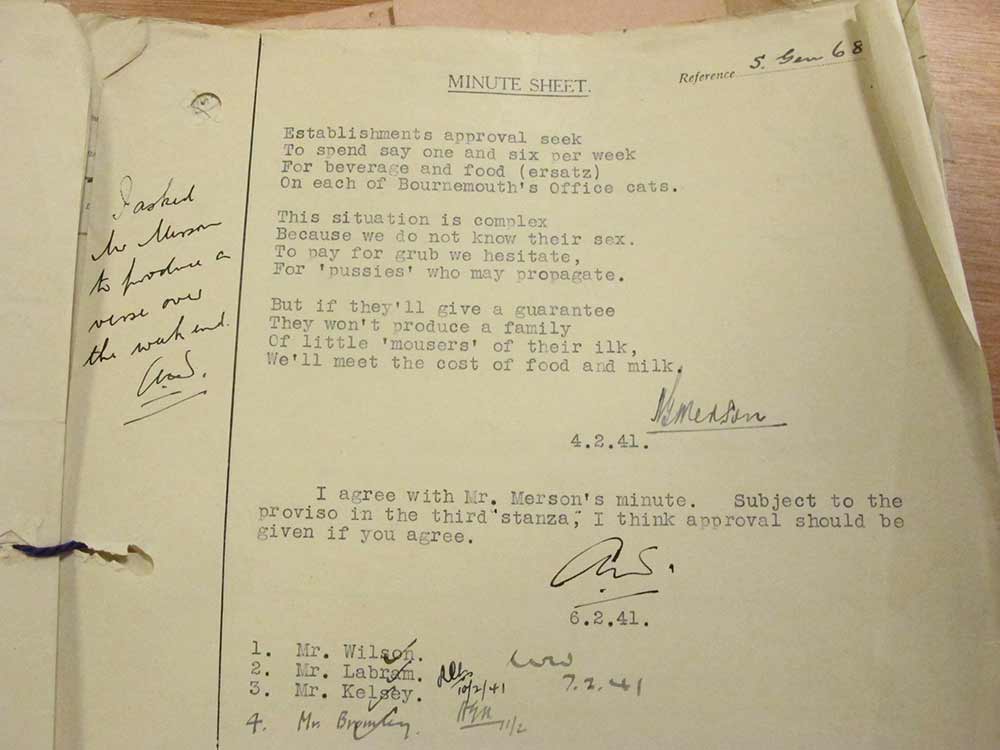

On his new diet, Peter performed his mousing duties admirably. When part of the Home Office moved to Bournemouth in the Second World War, Peter’s services were so missed they applied for an allowance for two cats. London agreed, with the poetic caveat that it be made sure the cats didn’t breed:

‘To pay for grub we hesitate

For ‘pussies’ who may propagate’

Poem in meeting minutes (catalogue reference: HO 223/43)

Peter II

Letter regarding the death of Peter II (catalogue reference: HO 223/43)

By 1946, Peter’s career was at an end. No longer fitting the bill for the Treasury’s allowance for ‘an efficient cat’ (Peter was 17 years old), he was put to sleep on 14 November 1946.

A month later he was replaced by a two month old male kitten, dubbed Peter II.

However, the second Peter was to have a tragically short tenure as the Home Office’s chief mouser. At 3.15am on 27 June 1947, Peter II was struck by a car while crossing the road from the Home Office to the Cenotaph. The RSPCA attended on the cat, but unfortunately advised that it was best for Peter to be put to sleep.

‘Peter the Great’

Peter II was succeeded in the role of Official Home Office Cat by the (imaginatively named) Peter III on 27 August 1947. Perhaps the best-loved cat the Home Office has ever had, he might be more appropriately referred to as ‘Peter the Great’.

Peter became somewhat of a celebrity, appearing on the BBC in 1958 and pictured in newspapers and magazine, including October 1962’s ‘Woman’s Realm’.

Peter’s salary became part of the national conversation, with many animal lovers and cat charities incensed that the Home Office only paid him enough for what they considered to starvation rations. The Office were, however, unmoved by these entreaties. Responding to a letter of concern in 1958 the Home Office assured the writer that:

‘The mice which Peter is employed to catch are not mere “perks”; they are intended to be, and should be, his staple food … Peter’s emoluments [salary] are not designed to keep him in food: if they were, they would also keep him in idleness.’

The writer also informs the concerned cat-lover that Peter was kind enough to leave a pigeon in his desk, adding that ‘the fact that, though chewed, it was not consumed, suggests he is not suffering from starvation.’

A condolence letter from Etti-Cat to Peter on his death (catalogue reference: HO 223/43)

Much of the Official Cats’ file is made up of replies to well wishers and cat-lovers, and these letters give us an insight into Peter’s daily life and character. In 1962 for instance we learn that while Peter doesn’t have any ‘cat-friends’ his hobbies include ‘pigeon fancying’ – those poor birds.

Peter III was put to sleep on 9 March 1964 and buried in April 1964 in the PDSA pet cemetery.

The Home Office received many letters of condolence from admirers of Peter from Britain and further afield, including one from the New York Transit authority’s ‘Etti-Cat’, a feline dedicated to promoting courtesy on the subway.

There is also quite a staggering number of letters from Italy, where Peter was clearly somewhat of a celebrity.

Peta

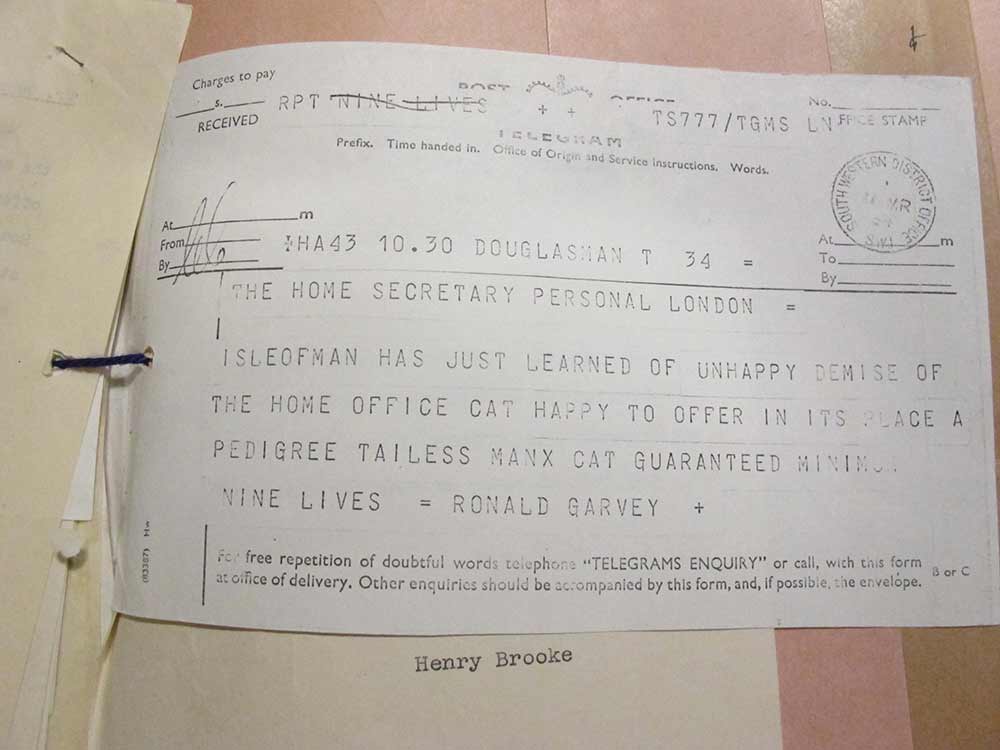

Two days after Peter’s death Ronald Garvey, Lieutenant Governor of the Isle of Man, sent a personal telegram to the Home Secretary expressing sympathy for Peter’s ‘unhappy demise’ but offering in his place a Manx cat ‘guaranteed minimum nine lives’.

Telegram from Lieutenant Governor of the Isle of Man, offering a Manx cat (catalogue reference: HO 223/43)

The Home Office wisely decided to accept the Manx offer – possibly to avoid a diplomatic incident that could have left both governments feeling decidedly catty towards the other…

The Manx cat, originally called Manninagh Katedhu but renamed Peta by the Home Office, was presented to the Home Secretary, Henry Brooke, on 7 May 1964. The exchange was attended by the BBC and several newspapers.

Before Peta’s arrival, it was decided to make some adjustments to the working conditions of the Home Office’s cat. A memo from 1 May 1964 points out that previous feline employees, having been provided by the office’s cleaners, were from ‘the industrial grades’, whereas Peta had a ‘diplomatic background’. It was suggested that she therefore be salaried, as opposed to paid weekly. Peta also received a salary increase – receiving a starting salary of £13 per annum, more than double her predecessor’s wage.

Peta, like her predecessor, proved popular with Home Office staff and the wider public as well. Receiving congratulations from other ‘bureauCATS’ from around the world on her appointment.

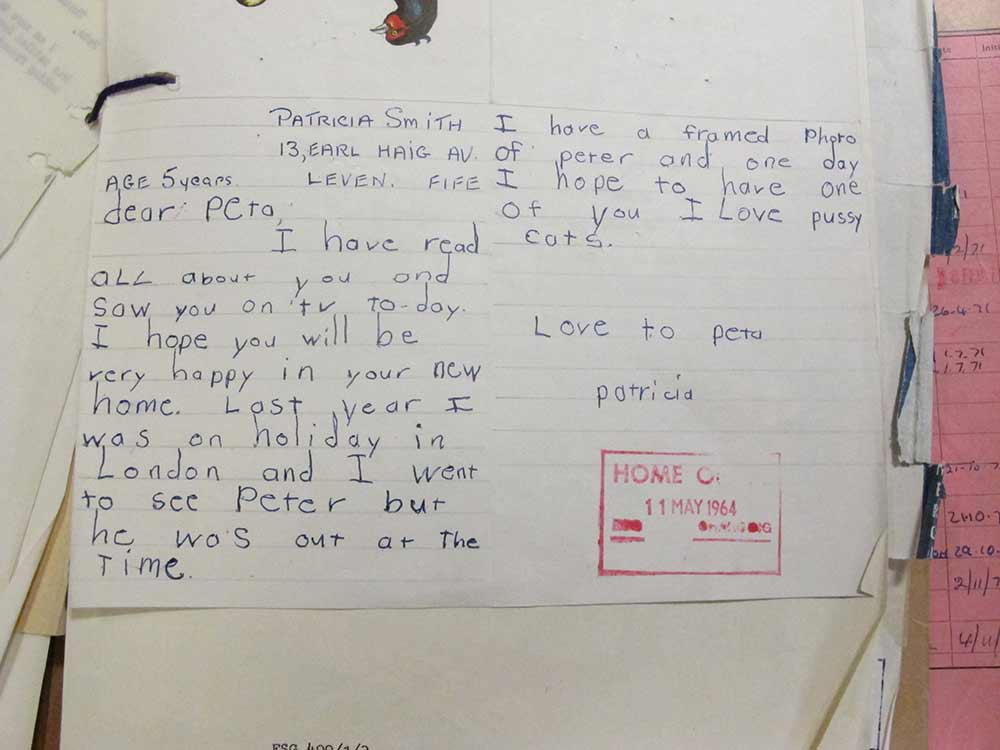

Peta’s file also preserves the messages she received from one particularly besotted correspondent, 5 year old Patricia Smith of Fife.

Patricia first wrote to Peta in May 1964 to welcome her and recount the story of how she had tried to visit Peter at the Home Office when on holiday in London (he was out at the time), as well as to request a photo of Peta.

Patricia Smith’s first letter to Peta (catalogue reference: HO 223/43)

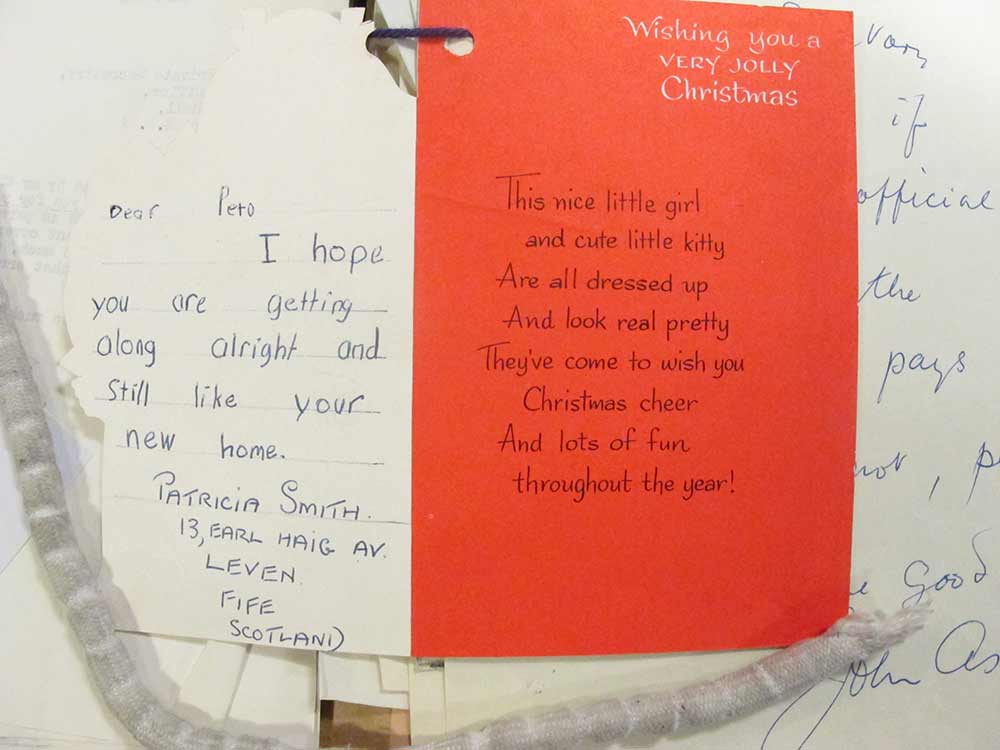

The same year, she sent Peta a Christmas card. Both are now preserved in the public record.

Patricia Smith’s first Christmas card to Peta (catalogue reference: HO 223/43)

Peta was a popular cat, but the indulgences this granted her proved to be her undoing. In February 1967 Home Office staff were castigated for feeding Peta endless titbits, which made her ‘inordinately fat’ and ‘lazy in her habits’. This jeopardised her house training, necessitating a programme of ‘re-education’.

Unfortunately, Peta didn’t reform her character. Again in 1967 she was accused of brawling with Nemo, Prime Minister Harold Wilson’s Siamese cat, leading to Mrs Wilson being injured. The Home Office’s cleaners and office keeper continued to complain of Peta’s behaviour and lack of house-training.

By 1968, internal Home Office memos begin to consider the unthinkable – putting Peta ‘out to grass’ – surely not!

Fortunately this was not a metaphor. Although it’s not quite clear when she left the corridors of power, a 1976 reply to an enquiry about Peta revealed that she was currently ‘enjoying a break in the country, where she can roam in a large garden belonging to a member of staff’. Peta died in 1980.

Updated/maj. 08-08-2022

Vues : 10